Why rice-wheat need to be de-hyphenated

By Harish Damodaran

Most economics commentators and policymakers tend to club wheat and rice, treating them as part of a “cereal surplus” and “mono-cropping/lack of diversification” problem. But today, the situations in the two crops are very different.

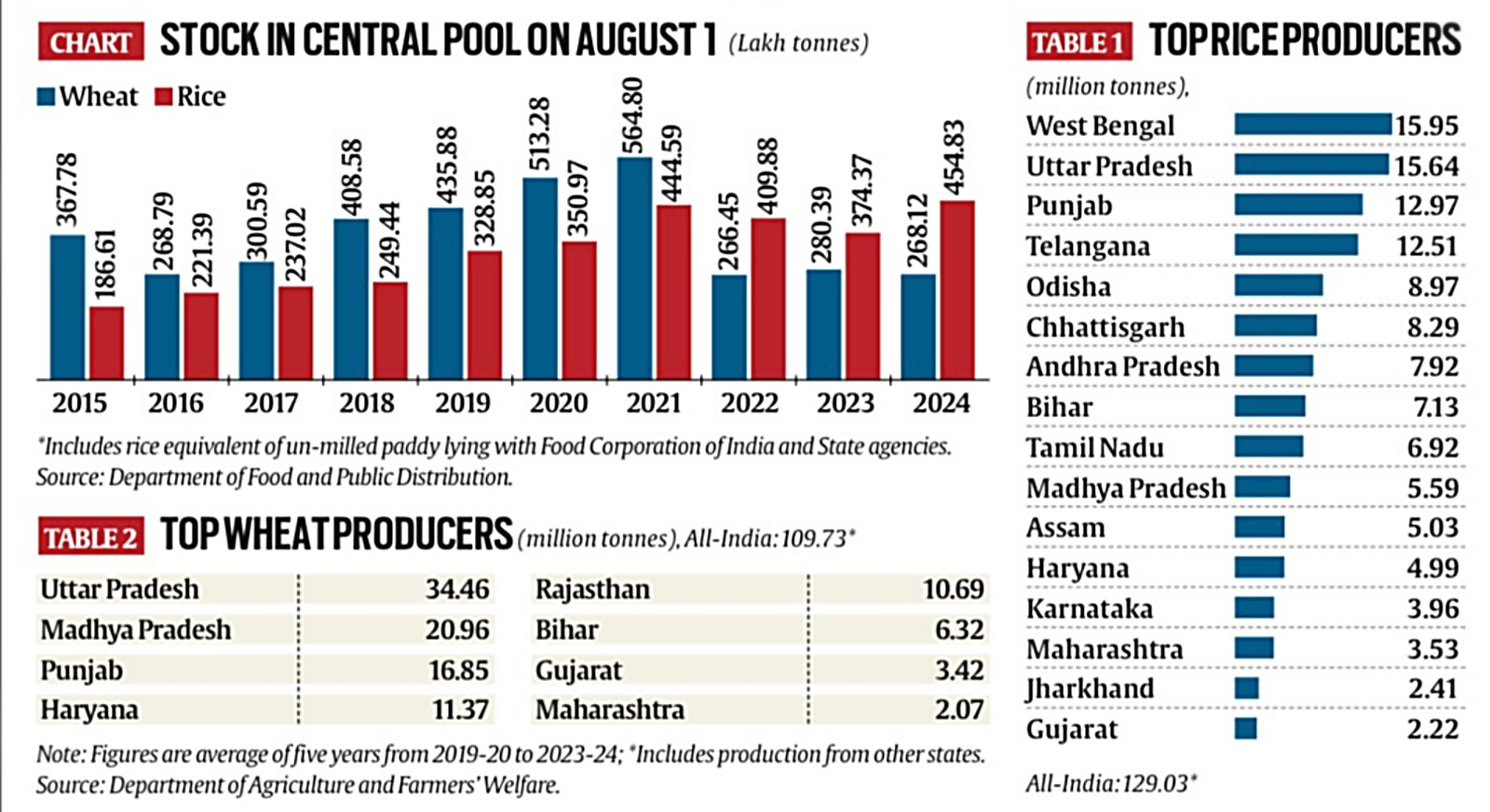

In rice, there is a surplus problem: India exported 21.21 million tonnes (mt) of the cereal grain (basmati plus non-basmati) in 2021-22, 22.35 mt in 2022-23, and 16.36 mt in 2023-24. Despite the record shipments, rice stocks in government godowns, at 45.48 mt on August 1, were at an all-time-high for this date.

Things have been the other way round for wheat, with exports plunging from a peak of 7.24 mt in 2021-22 to 4.69 mt in 2022-23 and 0.19 mt in 2023-24. The Union government actually banned wheat exports in May 2022. Yet, its Central pool stocks on August 1, at 26.81 mt, were the lowest for this date in recent times, after 2022 (26.65 mt) and 2008 (24.38 mt).

Usually, rice stocks are below that of wheat at this time of the year. This is because wheat is harvested and marketed during April-June, whereas the main kharif rice crop comes in only from October. The last three years have been unusual, with rice stock levels on August 1, at the tail-end of the crop marketing year, being higher than that of wheat (see chart).

Rice is grown both during the kharif (southwest monsoon) and rabi (winter-spring) seasons. Moreover, it is cultivated across a wide geography. Table 1 shows as many as 16 states producing 2 mt and more each — from Telangana and Tamil Nadu in the South to Uttar Pradesh and Punjab in North, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh in Central, West Bengal and Assam in East, and Maharashtra and Gujarat in West.

CHART: Stock in Central Pool on August 1; Top wheat producers; Top rice producers

CHART: Stock in Central Pool on August 1; Top wheat producers; Top rice producers

Wheat, by contrast, has a single rabi cropping season and only eight states producing 2 mt-plus each, all concentrated in northern, central and western India (Table 2). The big four alone (UP, MP, Punjab and Haryana) account for over 76 per cent of India’s output. Wheat is, thus, a temporally as well as geographically more constrained crop than rice. This is what makes its production relatively more volatile.

In rice, the main limiting factor is water availability. Take Telangana. With the spread of irrigation and farmers assured of a minimum support price for their crop, the state has emerged as India’s top rice producer, nearly quadrupling its output from 4.44 mt to 16.63 mt between 2014-15, and 2023-24.

Wheat, on the other hand, has become vulnerable to winters getting shorter, warmer and less predictable — perhaps due to climate change. Mercury spikes in March (when the crop is in grain formation and filling stage), or above-average November-December temperatures (during the sowing and vegetative growth period) have taken a toll on production in the last three years, reflected in depleted government stocks.

The divergence in consumption

While India’s wheat production is facing structural challenges — from temporal, geographical and climate-induced factors — consumption is growing.

Official household expenditure survey data for 2022-23 shows per capita monthly wheat consumption at 3.9 kg in rural and 3.6 kg in urban India, translating to roughly 65 mt for a population of 1,425 million. But this would only be wheat that is grounded into whole-grain flour (atta) or semi-processed semolina (sooji/rava), and consumed as basic bread (roti, chapati, paratha, poori), morning upma or even rava kesari/sooji halwa sweet dish at home.

An increasing share of wheat consumption is, however, happening in processed form using refined flour or maida. Whole wheat grain has three edible parts: an outer skin or bran (about 14 per cent of the kernel weight), an inner germ or embryo that can sprout into a new plant (2.5 per cent) and an endosperm rich in starch and gluten proteins (83 per cent).

The atta resulting from grinding whole wheat in traditional stone chakki mills contains all the three parts. Sooji/rava and maida are produced by roller flour mills (RFM) that remove the bran and germ. Sooji/rava is the coarse pale-yellow flour obtained from grounding the separated endosperm. Further grinding, filtering and bleaching yields the refined white maida flour.

Maida is the key ingredient in most bakery products (bread, bun, burger, biscuits, cookies, cakes and pastries), convenience foods (from sandwiches, noodles, pasta, pizza and momos to pav-bhaji, kulcha, samosa, kachori and pakora), and even sweetmeats such as gulab jamun and jalebi. Not for nothing that maida is known as all-purpose flour. It may lack dietary fibre, minerals, B vitamins, valuable proteins, and fat, which are lost in the refining process. But the stripping away of the bran and germ is what contributes to maida’s longer shelf life, apart from fine texture, softness, and stretchability, ideal for bhaturas, rumali rotis and Malabar parottas as well.

There’s no hard data on wheat consumption in the above processed forms. What is not in doubt is that it is increasing, and will continue to, with rising incomes and urbanisation. A similar trend isn’t visible in rice, where processing and convenience food innovations have seemingly not gone beyond idli, dosa, murukku twisting, puffed murmura, puddings or biryani dishes.

Policy implications

“An average South Indian today takes wheat in some form at least in one meal daily. Rice has not caught on in the North like wheat has in the South,” S Pramod Kumar, president of the Roller Flour Millers Federation of India, pointed out.

India has 1,500-odd RFMs processing anywhere from 50 to 500 tonnes of wheat a day into maida, sooji/rava, bran and germ. These are bigger than the stone chakkis — both roadside (their numbers are anybody’s guess) and organised (around 700) — that grind between 50 and 300 kg of wheat per hour (depending on motor power) to make whole atta flour.

Given a scenario of rising consumption and geography/climate-imposed production challenges, one can well imagine India turning into an importer of wheat. “That’s inevitable in the short term. For the long term, the government needs to focus on boosting per-acre yields, and breeding climate-smart varieties,” Kumar said.

It is the opposite with rice, where domestic consumption is not keeping pace with production. “The government should immediately lift the ban on exports of white non-basmati rice. The 20 per cent duty on parboiled non-basmati, and the $ 950/tonne floor price on basmati shipments must also go. Not doing so will create an unmanageable excess stocks problem,” Vijay Setia, former president of the All India Rice Exporters’ Association, told The Indian Express.

Either way, the time has come to de-hyphenate rice-wheat, and not conflate one with the other. The two cereals are grains apart in terms of issues faced, both current and for the future.

This article has been republished from The Indian Express.