Easing wheat, rising rice

By Harish Damodaran

Prices of wheat and rice have gone in opposite directions in the global market, one crashing and the other soaring.

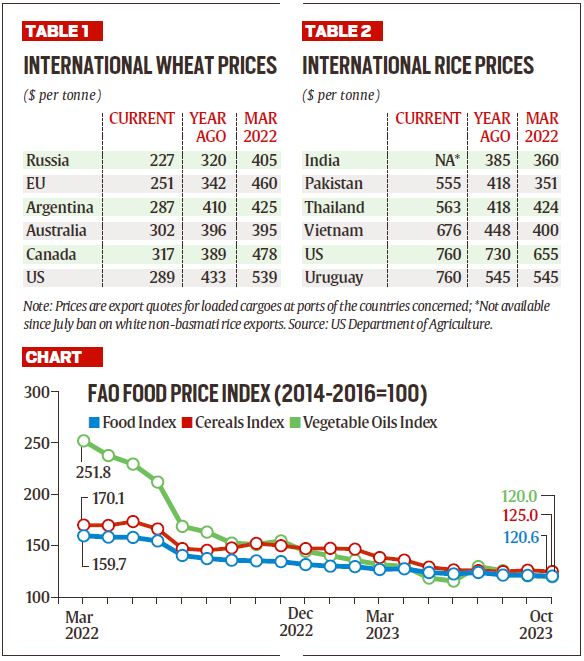

Wheat prices at the Chicago Board of Trade futures exchange hit an all-time high of $13.64 a bushel ($501/tonne) on March 8, 2022. That was days after Russia invaded Ukraine, with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index (FPI) touching a record 159.7 points in March 2022.

Prices of wheat have since more than halved to $5.75 a bushel ($211.4/tonne). The FPI — a weighted average of world prices of a basket of food commodities over a base value, taken as 100 for 2014-16 — has also fallen to 120.6 points in October 2023.

The declines have been sharper for the cereals and vegetable oils price indices — from 170.1 and 251.8 points to 125 and 120 points respectively — between March 2022 and October 2023. (See chart)

Situation in wheat

Wheat from Russia is being exported currently at $227 per tonne free-on-board, i.e. from the port of origin. Ocean freight and insurance charges will take the cost at Indian ports to $265-270 per tonne or Rs 2,200-2,250 per quintal. That’s just under the Rs 2,275/quintal minimum support price declared by the Union government for the 2023-24 wheat crop that is being sown now.

After adding port handling-cum-bagging (Rs 200) and internal transport (Rs 100-150 from Tuticorin or Krishnapatnam), imported Russian wheat would cost Rs 2,500-2600/ quintal at any flour mill in South India. That makes imports feasible, relative to a year ago.

Table 1 shows how export prices of wheat from different origins have slid from the March 2022 peaks. Much of it has been courtesy of Russia.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has projected the country’s wheat shipments at a record 50 million tonnes (mt) in 2023-24 (July-June), up from 47.5 mt and 33 mt in the preceding two years. Higher exports from the European Union (31.9 mt in 2021-22 to 37.5 mt in 2023-24), Canada (15 mt to 23 mt) and Kazakhstan (8.5 mt to 10 mt) too, will more than offset the reduced quantities from Ukraine (18.8 mt to 12 mt) over this period.

“Wheat availability has overall improved. Apart from international prices easing, the government has managed its own stocks very well,” S Pramod Kumar, president of the Roller Flour Millers Federation of India, said.

At 21.88 mt on November 1 this year, wheat stocks in government godowns were marginally above the 21.05 mt a year ago, though way below the 41.98 mt for the same date in 2021. From April 2020 to December 2022, the government supplied 10 kg of free or near-free rice or wheat per person per month through the public distribution system (PDS). With stocks depleting, the quota for PDS beneficiaries was cut — rather, restored — from this calendar year to the original 5 kg/ person/ month.

The government is at present channeling 1.2-1.3 mt of wheat per month (from 1.8-1.9 mt till last year) through the PDS. Simultaneously, in order to cool market prices, it has resorted to selling from the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) stocks. Such open market sales, at a minimum auction reserve price of Rs 2,125/ quintal, have increased from 0.2 mt to 0.3 mt per week from November 2023.

“Even if they step up the weekly open sales to 0.5 mt from January (2024), and maintain PDS supplies at 1.2-1.3 mt per month, FCI warehouses would have 7-7.5 mt of wheat stocks on April 1, which is close to the required minimum buffer of 7.46 mt for that date. By then, the new crop will also arrive in the market,” Kumar said.

It’s tighter in rice

In wheat, the flexibility to import is an added comfort. It’s another matter whether the government will allow imports, with national elections scheduled in April-May 2024. Any move to slash/ scrap the 40% import duty on wheat may face opposition from farmers across North and Central India.

In rice, even that limited flexibility for imports does not exist. This is because India is the world’s No. 1 exporter of rice, its share in the global trade having ranged from 36.6% to 40.7% in the last three years, according to USDA data. The world’s biggest exporter cannot also be an importer.

Unlike the situation in wheat, global export prices of rice today are higher than a year ago, or in March 2022. (Table 2) The reason is the restrictions India has put on exports. The Narendra Modi government has, since July 2023, banned exports of all white non-basmati rice. Only basmati and parboiled non-basmati rice shipments are being permitted, while being subjected to a $950/ tonne minimum export price (MEP) stipulation and 20% duty respectively.

India’s position in the international rice market is similar to Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s in palm oil or Ukraine’s and Russia’s in sunflower. Supply disruptions from these large exporters tend to not only push up world prices, but to also produce a domino effect. India’s rice export curbs have benefited Pakistan, which is expected to ship out 5 mt this year, much more than the 3.6 mt in 2022-23.

But the Pakistan government too, last week, fixed floor prices below which no rice can go out. These MEPs — from $450/tonne on 100% broken rice to $900/tonne on white, parboiled, and steamed basmati — are aimed at preventing domestic supply shortfalls.

Implications for inflation

India’s cereal inflation averaged 10.65% year-on-year in October, based on the latest official consumer price index numbers. That was more than the 4.87% general retail inflation and the 6.61% annual rise in consumer food prices for the month.

Inflation in both rice and wheat are mainly a function of domestic production. While Russia’s flooding the world with cheap wheat has made imports more economically viable, electoral considerations render it politically not-so-feasible.

It’s quite the opposite in edible oils, where India meets roughly 60% of its consumption needs through imports. In the marketing year ended October 2023, vegetable oil imports reached an unprecedented 16.71 mt, as against 14.41 mt in 2021-22.

But the global price collapse — due to normalisation of supplies from Indonesia and Russia-Ukraine — led to imports falling from $19.60 billion in 2021-22 to $16.65 billion in the 2022-23 oil year, according to the Solvent Extractors’ Association of India. And retail edible oil inflation, not surprisingly, was at minus 13.73% in October.

The course of cereal inflation, by contrast, would be determined primarily by the size of the crops harvested by Indian farmers.

This article has been republished from The Indian Express.